Video Player is loading.

Current Time 0:00

/

Duration 0:00

Loaded: 0%

0:00

Stream Type LIVE

1x

- 0.5x

- 0.75x

- 1x, selected

- 1.25x

- 1.5x

- 1.75x

- 2x

- Chapters

- descriptions off, selected

- captions settings, opens captions settings dialog

- captions off, selected

This is a modal window.

Beginning of dialog window. Escape will cancel and close the window.

End of dialog window.

10 seconds

Playback speed

This is a modal window. This modal can be closed by pressing the Escape key or activating the close button.

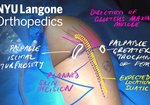

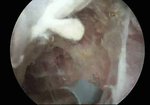

Symptomatic proximal hamstring tendon tears are typically repaired surgically, with open incision and knot-tying technique. ...

read more ↘ An endoscopic, knotless, suture-bridge repair technique is presented. Potential advantages include knotless simplicity, compression over a broad zone to improve tendon–bone healing, and decreased pain secondary to elimination of knots and the open incision and approach.

This technique can close a treatment gap for patients who have high-grade, partial-thickness tears, with significant symptoms despite sufficient conservative treatment and time (P.T., activity modifications, +/- PRP injection), yet are hesitant to proceed to open repairs. My experience is overall patients have much less pain, quick return to tolerance of daily activities such as sitting and standing, and most noticeably there is no large incision where the patient will sit on to induce discomfort (which dissipates, but not always completely, and the discomfort can last for life).

Such a clinical scenario also presents a technical-advancement opportunity for the surgeon interested to offer endoscopic repairs: the tendon is nondisplaced, scarring is minimal to none, the sciatic nerve is reliably identified and safely away from repair site, and repairs are surgically much easier to perform than acute, displaced tears with hematoma and scarring.

Even if the surgeon initially places the anchors endoscopically and then pass sutures through the tendon and tie knots through a mini-open incision, the endoscopic start to the procedure can save plenty of OR time and effort to expose and directly see the ischial tuberosity, when the endoscopic view can be obtained quite quickly, sometimes within a few minutes. As experience with endoscopic start to the procedure grows, the surgeon will quickly feel comfortable performing the entire procedure endoscopically.

↖ read less

read more ↘ An endoscopic, knotless, suture-bridge repair technique is presented. Potential advantages include knotless simplicity, compression over a broad zone to improve tendon–bone healing, and decreased pain secondary to elimination of knots and the open incision and approach.

This technique can close a treatment gap for patients who have high-grade, partial-thickness tears, with significant symptoms despite sufficient conservative treatment and time (P.T., activity modifications, +/- PRP injection), yet are hesitant to proceed to open repairs. My experience is overall patients have much less pain, quick return to tolerance of daily activities such as sitting and standing, and most noticeably there is no large incision where the patient will sit on to induce discomfort (which dissipates, but not always completely, and the discomfort can last for life).

Such a clinical scenario also presents a technical-advancement opportunity for the surgeon interested to offer endoscopic repairs: the tendon is nondisplaced, scarring is minimal to none, the sciatic nerve is reliably identified and safely away from repair site, and repairs are surgically much easier to perform than acute, displaced tears with hematoma and scarring.

Even if the surgeon initially places the anchors endoscopically and then pass sutures through the tendon and tie knots through a mini-open incision, the endoscopic start to the procedure can save plenty of OR time and effort to expose and directly see the ischial tuberosity, when the endoscopic view can be obtained quite quickly, sometimes within a few minutes. As experience with endoscopic start to the procedure grows, the surgeon will quickly feel comfortable performing the entire procedure endoscopically.

↖ read less

Comments 0

Login to view comments.

Click here to Login